Discourse graphs could significantly accelerate human synthesis work

Authored By:: Joel Chan

An exciting hypothesis that motivates this work is that making discourse graphs widely available could accelerate human synthesis work, and thereby accelerate innovation and scientific discovery.

To understand why this information model might augment synthesis, consider a researcher who wants to understand what interventions might be most promising for mitigating online harassment. To synthesize a formulation of this complex interdisciplinary problem that can advance the state of the art, she needs material that can help her work through detailed answers to a range of questions. For example, which theories have the most empirical support in this particular setting? Are there conflicting theoretical predictions that might signal fruitful areas of inquiry? What are the key phenomena to keep in mind when designing an intervention (e.g., perceptions of human vs. automated action, procedural considerations, noise in judgments of wrongdoing, scale considerations for spread of harm)? What intervention patterns (whether technical, behavioral, or institutional) have been proposed that are both a) judged on theoretical and circumstantial grounds as likely to be effective in this setting, and b) lacking in direct evidence for efficacy?

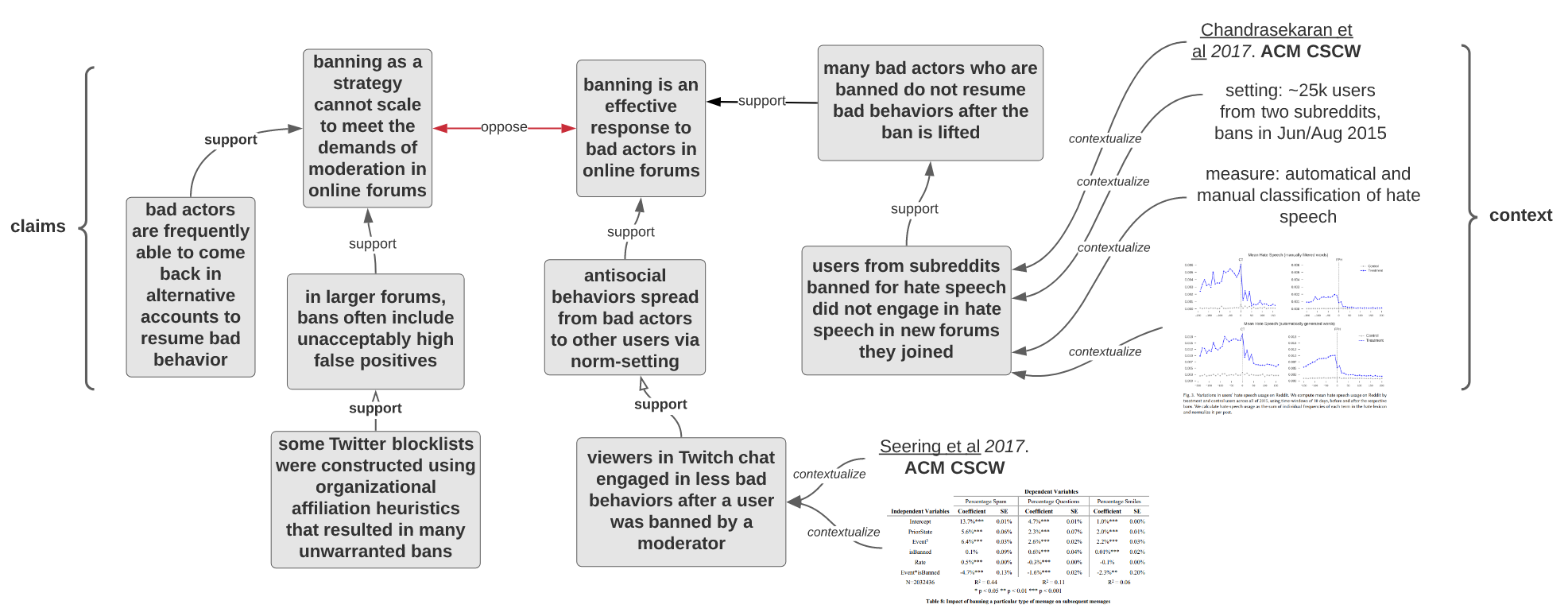

The answers to these questions cannot be found simply in the titles of research papers, in groupings of papers by area, or even in citation or authorship networks. The answers lie at lower levels of granularity: the level of theoretical and empirical claims or statements made within publications. For example, “viewers in a Twitch chat engaged in less bad behaviors after a user was banned by a moderator for bad behavior”, and “banning bad actors from a subreddit in 2015 was somewhat effective at mitigating spread of hate speech on other subreddits” are claims that interrelate in complex ways, both supporting other claims/theories that are in tension with each other.

This level of granularity is crucial not just for finding relevant claims to inform the synthesis, but also for constructing more complex arguments and theories, by connecting statements in logical and discursive relationships.

Beyond operating at the claim level, our researcher will also need to work through a range of contextual details. For example, to judge which studies, findings, or theories are most applicable to her setting, she needs to know key methodological details including the comparability of different studies’ interventions, settings, populations, and outcome measures. She might need to reason over the fact that two studies that concluded limited efficacy of bans had ban interventions that were quite short, on a forum with no identity verification. Or she might reason through the fact that a prominent theory of bad faith and discourse was proposed by a philosopher from the early 2000’s (before the rise of modern social media). To judge the validity of past findings (e.g., what has been established with sufficient certainty, where the frontier might be), she would need to know, for example, which findings came from which measures (e.g., self-report, behavioral measures), and the extent to which findings have been replicated cross authors from different labs, and across a variety of settings (e.g., year, platform, scale).

# Hypothesized individual benefits: Creative synthesis and exploration

A discourse graph as a data structure has key affordances that are hypothesized to enable just these sorts of synthesis operations. Information is represented primarily at the claim or statement level, and embedded in a graph of relationships with other claims and context. In a discourse graph, claims have many-to-many relationships to support composition of more complex arguments and theories, or “decompression” into component supporting/opposing claims. Contextual entities and information, such as methodological details and metadata, are explicitly included in the discourse graph. This supports direct analysis of claims with their evidentiary context, supporting critical engagement, integration, and even reinterpretation of individual findings. The following figure shows how this might be supported in the specific worked example above. Note that discourse graphs need not be represented or manipulated in this visual format; the underlying graph model can be instantiated in a variety of media, such as hypertext notebooks, and also implicitly in various analog implementations that allow for cross-referencing. What is important is the information architecture of representing networks of claims and their context.

Beyond the theoretical match between the kinds of queries scientists need to run over their evidence collection for synthesis, a discourse-centric representation that encodes granular claims instead of document “buckets” could facilitate exploration and conceptual combination. There is theoretical precedent for this in research on expertise and creative problem solving, where breaking complex ideas down into more meaningful, smaller conceptual “chunks” may be necessary for creative recombination into new conceptual wholes.1 Removing contextual details (though not losing the ability to recover them) may also be necessary and useful for synthesizing ideas and reusing knowledge across boundaries.2

At the same time, constructive and creative engagement with contextual details, is thought to be necessary for developing novel conceptual wholes from “data”, such as in sensemaking,3 systematic reviews,4 or formal theory development.5 This is a more specific application of the general insight that Context is necessary for knowledge reuse. Further, accurately predicting just which contextual details are necessary to represent directly in an information object is a difficult task6 that may be functionally impossible in creative settings.

The conjunction of these affordances — having both granular information objects like claims, and the ability to progressively expand their context by traversing/retrieving from the discourse graphs — may help to resolve this tension between granularity and contextualizability. For instance, graph-model and hypertext affordances like hyperlinking or transclusion might enable scientists to hide “extraneous details” (to facilitate compression) without destructively blocking future reusers from obtaining necessary contextual details for reuse.6

# Hypothesized collective benefits: Reduced overhead, and enhanced creative reuse

Discourse graphs (or parts thereof) could also significantly reduce the overhead to synthesis through reuse and repurposing over time, across projects, and potentially even across people.7 For example, imagine collaborators sharing discourse graphs with each other, rather than simple documents full of unstructured notes, to speed up the process of working towards shared mental models and identifying productive areas of divergence; or a lab onboarding new researchers not with long reading lists, but with discourse graph subsets they can build on over time. How much effort could be reduced if this were a reality?

The same affordances of discourse graphs around granularity and contextualizability that are hypothesized to augment individual synthesis should also facilitate exploration and reuse of an evidence collection that was created by someone else, or by oneself in the past. For example, granular representation of scientific ideas at the claim level is a much better theoretical match for the kinds of queries that scientists want to ask of an evidence collection during synthesis.8

These claims may also be more to the level of processing required to be understood and reused by others, compared to raw annotations and marginalia.9 Also, ambiguity around concepts can be a significant barrier to reuse across knowledge boundaries. For example, keyword search is only really useful when there is a stable, shared understanding of ontology:10 this condition is almost certainly not present when crossing knowledge boundaries11 and perhaps not even within fields of study with significant ongoing controversy amongst different schools of thought 12

In these settings, judging that two things are “the same” is problematic and difficult task; doing so without engagement with context can sometimes introduce more destructive ambiguity, not less, a hard-won lesson from the history of Semantic Web,13 ontology14 and classification efforts.15 A discourse-centric graph that embeds concepts in discourse contexts, traversing through networks of contextual details (such as authors, measures, contexts), and perhaps augmented by formal concepts as hooks, may be a better match for exploring ideas across knowledge boundaries. Further, although in many instances of knowledge reuse, contextual details tend to vary substantially across reuse tasks,16 there might be sufficient overlap of useful contextual details (e.g., participant information, study context) that remain stable across reuse tasks.17

Achieving Both Creativity and Rationale, The minds eye in chess Constraint relaxation and chunk decomposition in insight problem solving, Innovation Relies on the Obscure ↩︎

Institutional Ecology Translations and Boundary Objects, Ambiguity and Engagement ↩︎

Theoretical musings, Theory Before the Test, Are theoretical results Results, Darwin on man A psychological study of scientific creativity ↩︎

Organizational Memory as Objects Processes and Trajectories, Beyond Boundary Objects ↩︎

Rob comment: In case it was not clear the gravity of what’s being communicated here: this is learning through portfolio effects at scale, spread across people. This drastically reduces the amount of work necessary to synthesize solutions to new problems. This could rapidly accelerate the pace of innovation, as discussed in Discourse graphs could significantly accelerate human synthesis work. ↩︎

Micropublications a semantic model, From Proteins to Fairytales, ScholOnto an ontology-based digital library server for research documents and discourse ↩︎

Exploring the Relationship Between Personal and Public Annotations ↩︎

Reasons for the use and non‐use of electronic journals and databases ↩︎

Rob comment: Keyword searches can also be useful when there is a system in place to help people new to the domain learn a new ontology. See Information Foraging Video. ↩︎

In Defense of Ambiguity, Digital Futures Sociological Challenges and Opportunities in the Emergent Semantic Web ↩︎

What is a Distributed Knowledge Graph, Distributed ontology building as practical work ↩︎

Organizational Memory as Objects Processes and Trajectories, Sharing Knowledge and Expertise The CSCW View of Knowledge Management ↩︎