Synthesis as a process is usefully modeled as a specialized form of sensemaking

Authored By:: Joel Chan

While the most common manifestation of synthesis is an academic literature review, the underlying cognitive processes are not so different from what people do all the time: sensemaking.

Sensemaking as a model of a core cognitive process has a long history in cognitive and information science. We draw specifically on a family of models that describe sensemaking as an iterative search for representations of input data that can make some task easier (Towards a comprehensive model of the cognitive process and mechanisms of individual sensemaking, The Cost Structure of Sensemaking, The sensemaking process and leverage points for analyst technology). Examples include categorization schemes and comparison tables to facilitate decision-making about what camera to buy, a map of hypotheses for intelligence analysts, and an effective literature review of an area of research.

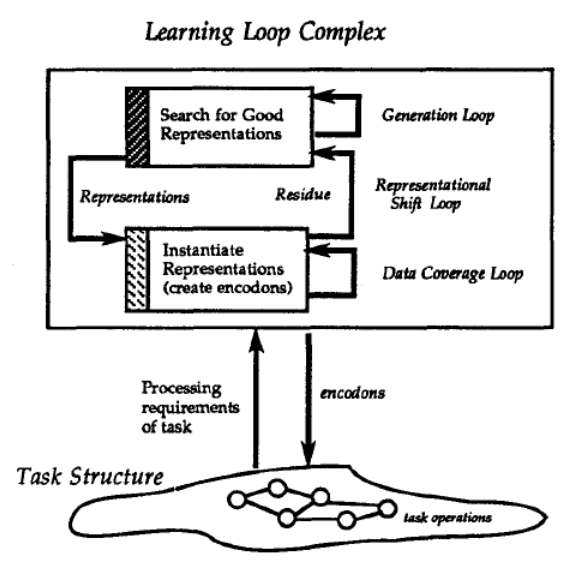

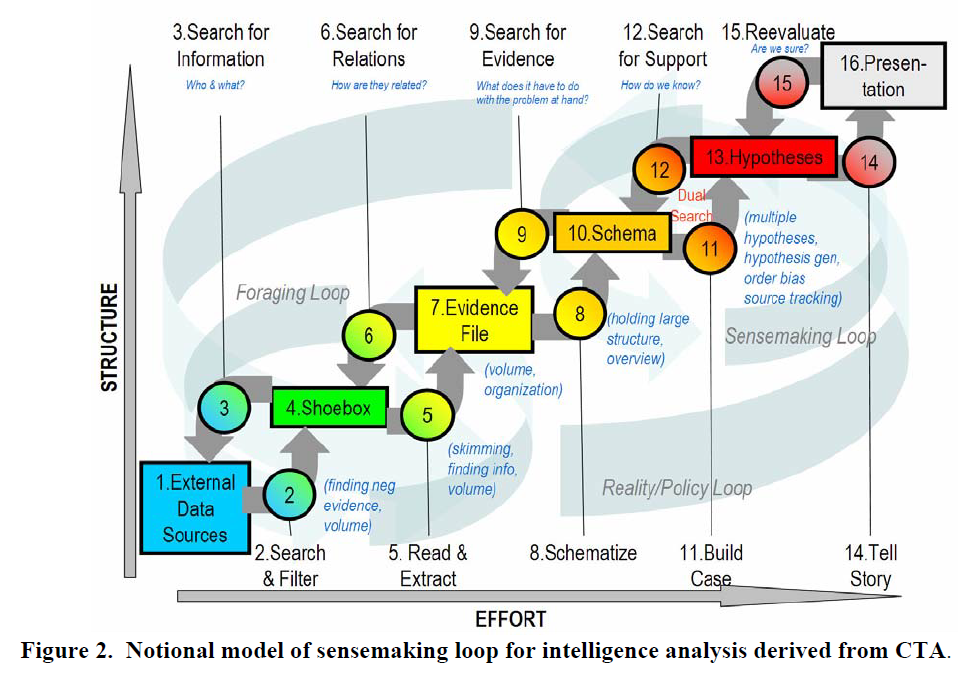

One crucial insight from models of sensemaking informs our research on synthesis: sensemaking involves iterative loops between searching (for data, useful representations) and analysis/composition (classifying data, composing data into representations). This is illustrated well in the following two figures from following figure from Russell et al’s Learning Loop Complex and Pirolli et al’s Notional Model of Sensemaking:

One implication of this insight are that search is a fundamental primitive of synthesis workflows because of the key involvement of search in this process model. Another implication is that Synthesis tools need to support incremental formalization to accomodate constant changes to the representation that are common with open-ended exploratory sensemaking like intelligence analysis (in contrast to well-trodden sensemaking tasks like deciding what camera to buy).

While sensemaking is a reasonable general model of the kind of work that is needed to do synthesis, there are likely to be key differences between synthesis and sensemaking, and other everyday tasks of sensemaking, due to the nature of the inputs (complex research papers, theories, findings) and the nature of the output (a boundary-pushing novel conceptual whole with no obvious precedent). These differences are likely to be consequential for understanding precisely what data structures and user interactions can optimize sensemaking for synthesis, since the process and representational requirements of sensemaking (e.g., whether the representation that is constructed has the shape of a map or timeline or argument, how much iteration and search for representations must happen) vary as a function of the task. Thus, our project tackles core research questions about the workflows and data structures that optimize synthesis, and how to build on this for decentralized synthesis. Some hypotheses include the importance of search as a primitive, and the importance of design patterns like incremental formalization and flexible compression.

Understanding how people perform synthesis is one of our open questions going into user interviews.